A proposal for a studio, a venue and a public space for new music within Melbourne’s Arts Precinct.

This thesis asks: can architecture facilitate the flourishing of the independent music scene, and certify the continued creation and evolution of new music as an engrained locational, cultural service?

It’s clear - through the evaluation of the experiences of independent artists - that the commodification and mass market promotion of music has limited the influence of local scenes. As such, small artists struggle to break through.

This project seeks to rehabilitate the cycle of musical invention: a loop of inspiration, composition, performance, recording AND consumption in a robust scene, where artists are inextricable from their context, and community. The starving of opportunities for expression of this latent new music demands a place for performance and recording. This manifests in the proposal for a studio and venue respectively

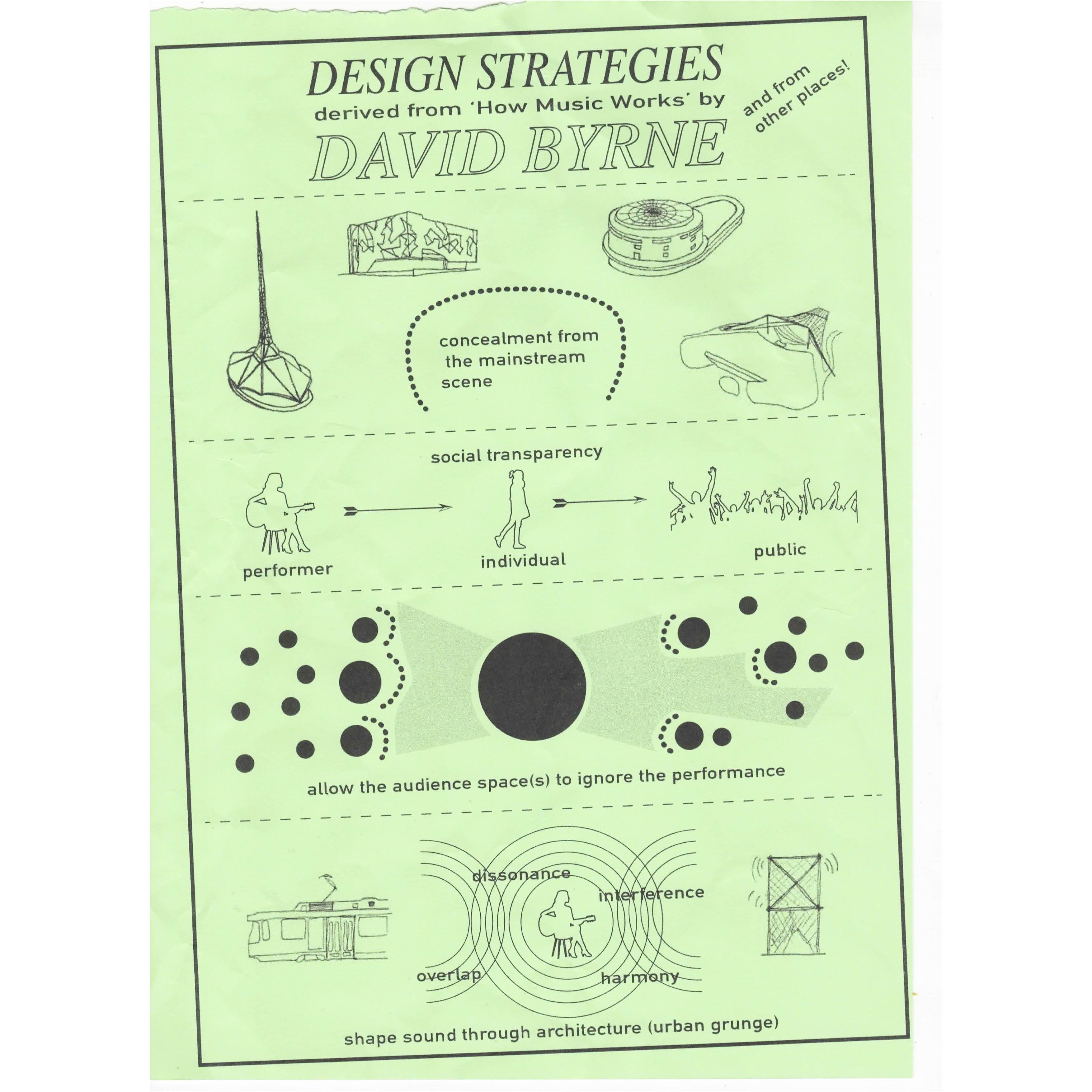

This thesis follows the principle of Creation Through Context as explained by the venerable David Byrne. The ways in which each building exists is interrogated through the lens of ‘influence on the state of the art’, in this way taking a stance against the stagnation of music as a commodity, instead with an emphasis on locality and experience - this is how a scene is built, and the design methodology that follows is influenced by Byrne’s concepts.

Click for project details.

The passive studio building on the south end of the site, and the porous venue against Princes bridge bound the public space and make it accessible, which in turn serves to weave these provisions into the urban context. This place as a whole must embed itself into the general consciousness in order to foster a new music scene: a local, relevant institution.

The studio building is designed to accommodate a range of methods of recording, whether solo, with a band or with a large ensemble, taking advantage of the wealth of musical expertise in Melbourne’s existing arts precinct while remaining adaptable to new sounds and methods with large, non-prescriptive recording spaces.

The double glazed curtain wall facade and interior walls offset by a wide corridor creates transparency while preserving acoustic separation, allowing the public to see into the process of music creation without compromising the musicians’ need to focus. Social transparency serves to foster a music scene, strengthening the connection between the artist and their art, and the artist and the consumer.

This allowance for new artists to record within the civic landscape must be complemented by a place for live performance, where new music can be shaped by its physical context and community, evolving what is a commitment to a static recording into a dynamic, ever-changing scene with a feedback loop of influence and invention - a new sound.

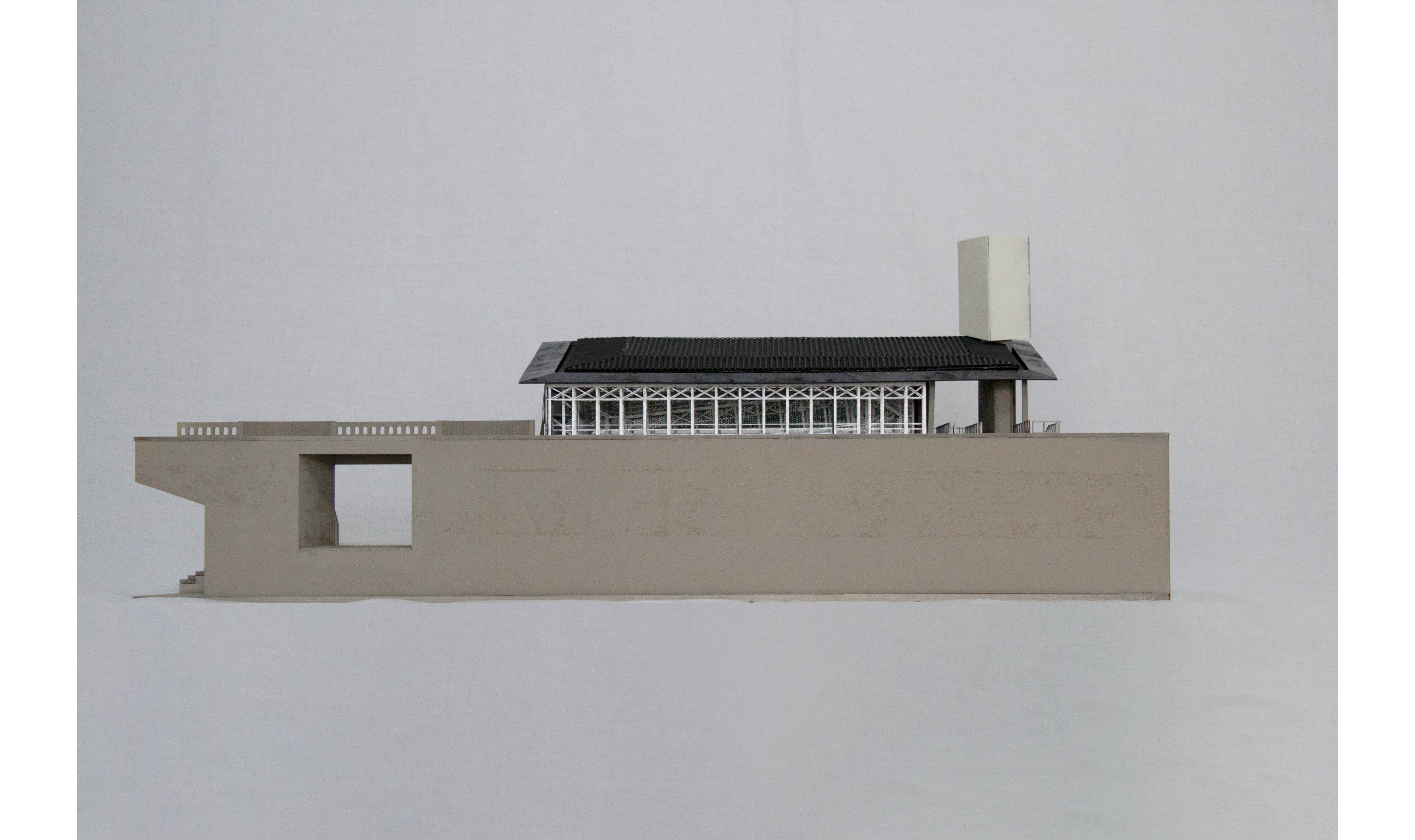

The venue carves itself a niche within the urban landscape while preserving the slope down to the lawn from St Kilda road. It preserves a path down into the public space at river level through its abundance of circulation paths downward from the bridge.

The south side of the building is structurally solid: a concrete anchor containing amenities and storage. The counterpoint is the scaffolded walkways and viewing platforms flanking the ground-level standing room. This building utilises the language of the temporary in an intentionally permanent provision for new music. This is the language of the urban grunge, speaking to the ability of architecture to influence the music performed within.

So, what will this new music sound like when it’s influenced by this architecture? The venue’s location makes it so that intrusive noise is abundant: cars, trams, boats, planes, helicopters, wind, rain… the public - the venue exists within the urban grunge.

It then follows that for the insurance of a locational, engrained music scene, this grunge should extend into the building itself: the creaky floorboards, the rattly steel scaffolds, the blowing of mesh screens and the reverberant concrete floor speak to a sound contingent on this oppressiveness.

Does the new sound try to yell over the top of it? Does it try and find respite in the urban bustle? Any new music performed in the venue has a dialogue with the city itself, fostering a highly locational, radically urban music scene influenced by architecture. This contextuality does much for the resilience of such an institution: new, local artists will continue to break through in a scene that speaks to and emphasises the spatiocultural aspects of the city’s urbanism, weaving itself into the general consciousness in time.

There is an implicit need for burgeoning scenes are concealed from the mainstream musical landscape, relevant in a place steeped in Melbourne’s mainstream arts culture which is encapsulated by the many nearby buildings, like Hamer Hall and the Arts Centre.

The green construction mesh implies a work in progress, but is really a functional partition, disallowing sightlines or circulation depending on the wants of performers. This concealment need not be literal, however. The offer of an ‘alternative’ scene suggests a more democratic, adaptable institution outside of the prevailing culture.

In spatial planning and affordance, the venue contrasts the deterministic layouts of Hamer Hall and the Arts Centre, instead offering no defined seating arrangement. The standing area is sloped, presenting an equitable viewing experience wherever an individual is on the floor. In extension, the perimeter walkways provide sight lines down into the performance from a multitude of angles.

Byrne endorses a space where an audience is allowed to ignore the performance in the venue, assisting in building a scene by enabling an audience to simply be immersed in the music, not completely attentive to it, as would be the case in a determinate venue. The public can choose their angle and experience. As such, the outer walkways will be obstructed when the venue is full, giving people the ability to ignore the performance, while the inner, sloped walkways are intensified by an audience with intent.

The venue distinguishes itself through this act, democratising the act of music consumption such that new music can become essential, and engrained in civic life, not separate from it.

In addition and following the principle of social transparency, there is no ‘back stage’. Instead, awaiting performers are encouraged to wait in plain view amongst the audience - they may become the audience. Musical influence is reciprocal. Since every new artist is influenced by this shared architectural condition, the social bonds between artists, and between artists and the audience is strengthened, always pushing the scene forward.

In order to embed this place - a local institution of new music - within the urban fabric, the place must account for a range of modes and levels of performance. It may be linear: musicians working up from busking on the streetside, to playing to a live audience within the venue, to pulling large crowds outdoors, or they may choose to remain routine buskers, or regular, integral performers.

The venue’s adjacency to Princes Bridge provides a setback and eave, mirroring that of Hamer Hall - a stage for buskers and street musicians to perform sporadically to an audience of passersby. They may or may not engage, but this is the most democratic space: a living billboard. This is the most casual, smallest level of performance.

On the other end of the scale, the river-level public space can be a passive sound stage, with sounds of practice or performance emanating from the buildings that bound it. Or, it could be active, with large, scheduled performances imposing themselves physically upon the city. While outdoors, this performance is determinate and demands attention in contrast to the streetside.

The venue is the stage with the greatest intent. Concealed and contained, the performers’ energy and music is amplified by the intent of a more driven audience, the core of the scene. These opportunities afford new artists the ability to find their musical footing and choose their pathway. The new sound will not be homogenised, however its contextual roots will be consistent, ensuring its continuation as long as there are those willing to engage.

To preach love, to express pain, to inspire protest, new music wants to work its way into the lives of individuals with which it resonates, and this project aims to let it. Whichever direction the art and artist go afterward can be moulded by the place - the architecture - in which this happens. The musicians take their music with them after inspiring the next, so that we are forever guaranteed ‘the new sound’.

Extended Thesis Statement

Can architecture facilitate the flourishing of Melbourne’s independent music scene, certifying the continued creation and evolution of new music as an engrained cultural service?

A proposal for studios, a venue and an acoustic, ambient civic square amidst the Arts Precinct for the flourishing of new music, furthering the democratisation of music creation and consumption as a cultural service.

This thesis follows the idea of creation through context. The ways in which any designed building, interior and civic space exists will be interrogated through the lens of ‘influence on the state of the art’. In this way, the project takes a stance against the stagnation of music as a commodity, instead with an emphasis on locality and experience.

The project will likely need to navigate the organicism of independent music creation and performance with the deterministic field of the city, offering facilities conducive to traditional methods while accommodating passive civic life, ultimately embedding the art form in the general consciousness.

Melbourne, as with most developed cities, is an architecture of the ‘event’ in reference to Jacques Derrida’s reading of Tschumi’s Parc de la Vilette: sinuous connections, chance encounters and temporal conditionality.1 Grassroots venues as well as community and public radio form the objects and the network respectively for independent musicians to express their art. In this way, the onus is on the willing consumer of art to seek it out, forming a cyclical process of new music creation, performance/recording and cultural impact. This is organic, genuine, and fragile. The unfortunate commodification of music in the general societal realm does not guarantee the continuation of this cycle, particularly through the domination of brazen, lucrative promotion, advertising and large performance in the public consciousness.

Richard Sennett in ‘The Open City’ recognises the reality of our brittle civic development: over-determination, segregation of function, and the homogenising of its population.2 The fragility of the cycle of new music is exposed through forces oblivious, indifferent or malicious, where music is marketed as a product, to a public treated as a single entity. Too often, we lose awareness of the individual within the commodified realm of the city. Artists are made part of the industry and people are made part of the crowd; every one-of-one becomes one in a million. Alternative scenes are both the patient and the remedy: wanting artists are disenfranchised through socioeconomic pains; the market prioritises revenue over culture; and there is a cratering of attention and recognition amongst the general public of burgeoning art outside the mainstream.3 An over-investment in independent music in the form of publicly funded studios (think a physical realisation of Triple J Unearthed) and an exemplary venue in a place embedded in public routine may work to remediate the disadvantages that the institution faces in Melbourne and its immediate surrounds.

The treatment of new music as an ‘institution’ is fraught, however. It comes with the danger of trivialising or diminishing the authenticity of the art itself, as I myself have duly recognised. As such, a dynamic approach must be taken to prevent the stagnation or unfortunate objectification of new music. It is not enough to solidify or seek to define an architectural or otherwise discernable language for music creation, since emulation of what has come before will be unsuccessful in the mission to rehabilitate the cycle. A ‘new’ venue and ‘new’ studios are inextricable from the ‘new’ music it seeks to foster. An understanding of the ways in which design influences and bolsters music is relevant in order to evaluate the success of any built or unbuilt form.

David Byrne in ‘How Music Works’ elucidates the potential effects of spatial context on music scenes during his time in New York - an ultimate urbanism.4 This is helpful when thinking about the embedding of such an institution in a civic context since, as noted, alternative scenes desire to be outside the prevailing culture. Therefore, this project becomes less about overt promotion to a public entity (as it once provocatively was), and more about a cultural service to those willing to listen. There remains a goal to sustain independent music, so a wider net must be cast, utilising Melbourne’s CBD and its people as a broad survey of sorts. People will be more likely to participate according to their own intent and interest, spurred on or catered to by a location conducive to transient public assemblage.

This location - Peppercorn Lawn opposite Fed Square on the south side of the Yarra - is void-like, in that it can be indeterminate due to its lack of urban programming. While it has the potential to be further intensified by linking it to Fed Square via a footbridge for example, this type of space need not be functional. The venue and studios may situate themselves here and be objects in a civic ambience. In this way, the ‘institution’ is no longer the focus, and is blurred by the circumstantial being of its location. At one moment and from a prevailing perspective, it is part of the city, but, at another time or in the minds of those in its grasp, it is its own system.

Ultimately, the ‘promotion’ or act of ‘getting the word out’ for new, independent musicians veers away from reference, and becomes much more implicit. Promotion follows and is the derivative of performance. There should not be any disconnection or severance of the art from the artist. When independent music as an institution is rightfully upheld, the music promotes itself, acting on its own without filtering or distillation into a trend or abstract concept. This space on the Yarra will respect this, emanating music, not describing it.

To instil joy, to express pain, to inspire protest, new music wants to work its way into the lives of individuals with which it resonates. Whichever direction the art and artist go afterward can be moulded by the place in which this happens. The musician takes the music with them. This project seeks to provide another place - a lifeline - to this institution within a network of places in and around the inner city, to the benefit of them all, continuing the cycle of creation ad infinitum.

Endnotes

1. Jacques Derrida, “POINT DE FOLIE — MAINTENANT L’ARCHITECTURE. Bernard Tschumi: La Case Vide — La Villette, 1985.” AA Files, no. 12 (1986): 65.

2. Richard Sennett, “The Open City,” Urban Age, published November 2006. https://urbanage.lsecities.net/essays/the-open-city.

3. Robert Leigh, “The Dying Notes: Australia’s Live Music Industry and Its Struggle for Survival,” Songwriter Trysts, published 7 June, 2024. https://www.songwritertrysts.com/trysts-news/australian-live-music.

4. David Byrne, How Music Works (Edinburgh, Great Britain: Canongate Books Ltd, 2012), 15.